The McDonald clan aboard Winter Solstice in 1981

The McDonald clan aboard Winter Solstice in 1981 When we returned to our "regular" education in school, we adapted to that intermission, completed some the courses we hadn't finished (I think I did grade 11 and grade 12 history at the same time), or in my older sister's case, took the extra time needed to complete the courses she wanted to have to graduate. We were changed by the experience, but we were in no way adversely affected by the time we took away from our formal education.

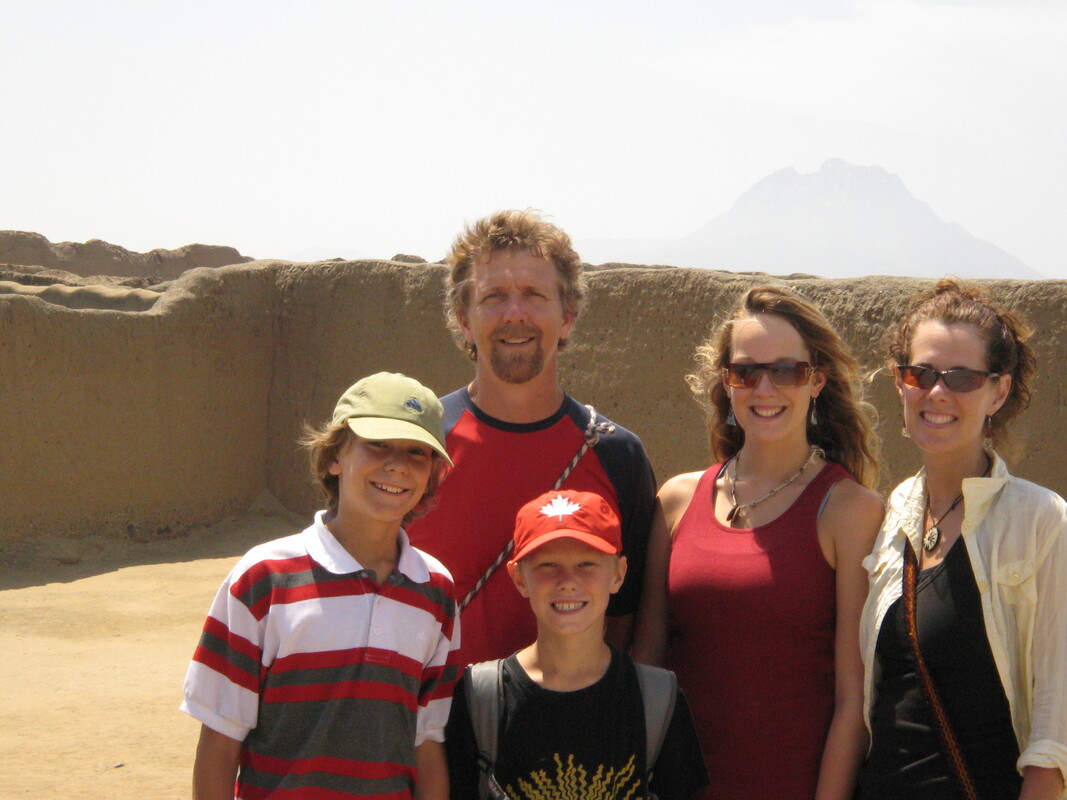

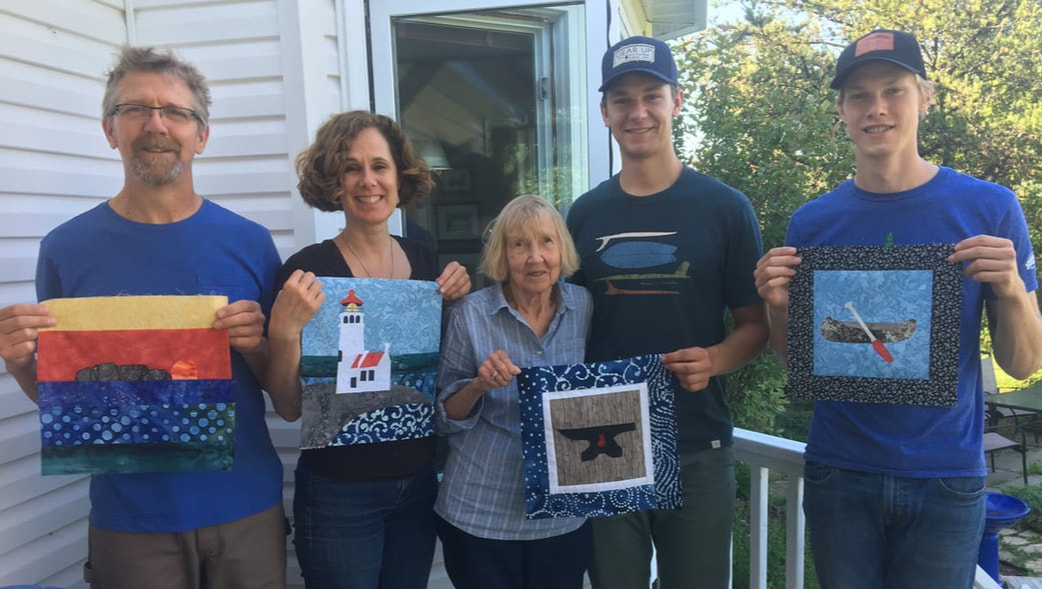

Flash forward a few years to 2007 when we decided to take our own kids on an adventure and backpacked around South America for six months. We did NOT take schoolwork with us, preferring that they engage in the experience. Admittedly, we were already homeschooling two of the three so were comfortable approaching learning in a different way. They have all gone on to succeed in their own way in their own time, with post-secondary education. They have all said they would not trade that time travelling for anything.

As we collectively respond to a global pandemic, governments are looking for ways to balance economic and social needs with responsible public health policy. I am not going to comment on those decisions. What I want to do is comment on our perception of what comprises an education and suggest that making a choice to teach/learn in a different way that may result in a child "losing" a year will not be the end of the world, or the end of that child's potential to succeed. I've been there. It can work, and work really well.

Are you choosing to send your child back to school? I support you. Are you choosing to keep your child at home? I support you. The emotional and physical needs of you and your child as you navigate the unique challenges of this pandemic are paramount. Having a different learning environment for academics for a year or two will not destroy your child's future. In fact, it may lead to some beautiful and creative opportunities. You've got this.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed